Leonardo Da Vinci’s Lost Bodies

Written by Jaillan Yehia

You probably already know that Leonardo da Vinci was one of the greatest artists to have ever lived, but the Italian inventor also made some startling discoveries about the human body which were light years ahead of their time – and subsequently lost to the world for nearly 400 years.

The Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace plunges you straight into da Vinci’s Renaissance world with an exhibition of his pioneering drawings on the human form, explaining the tragic reasons that Leonardo’s greatest project became nothing more than a footnote to history.

When Leonardo da Vinci decided to write a treatise on painting in the 1500’s it led him on a journey that would culminate in scientific discoveries which were so insightful, they would not be proved by modern medicine in some cases until the 1980’s.

As the main theme of Renaissance art was the human body Leonardo decided to devote a chapter of his treatise on painting to this theme. He soon realised that a chapter wasn’t going to suffice, so he decided to undertake a complete hands-on study of anatomy that would see him dissect both animal and human corpses.

His powers of visualisation were striking but he faced many challenges -his task required a combination of a strong stomach, good draughtsmanship, skill in drawing and perspective, geometrical and calculation methods, patience – and a great deal of time.

We learn also of the practical difficulties of da Vinci’s work – for example he suffered from a lack of female subjects meaning his drawings of the uterus are wrong, because he based them on a his observations of a cow, which needs much stronger muscles to hold the weight of a calf, than does a woman to carry a baby.

He also pioneered a rather gruesome technique of injecting molten wax into a brain before dissecting it so that he could understand the way the cavities worked before he started cutting it and destroyed them. He later used a similar technique to inject wax into an ox’s heart, then used the model to make a glass cast so he would have a fully functioning transparent model of the heart.

His bird dissections informed his ideas about flying machines which he returned to throughout his life and remains famous for to this day – using a proportional analysis of the different segments of the wing he copied the model in his own flying machine, having reduced the bird’s wing down to a system of parallel rods.

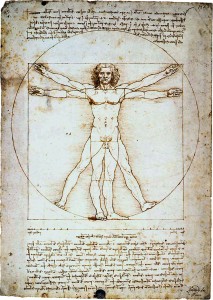

Despite these triumphs he didn’t manage to work out (and amazingly neither did anyone else until the 18th century) that lungs were not just there to cool the heart down and he was also confounded by the way the heart pumped blood, coming to an impasse in his understanding here. The most famous Leonardo da Vinci drawing in the world, The Vitruvian Man isn’t in the collection but represents another dead-end in Leonardo’s investigations, referred to by exhibition curator Martin Clayton as a red herring.

All of his dissection work did not go unnoticed, and despite the church approving the practice it was easy to suggest that Leonardo’s motives were not as they seemed; a nemesis appeared in the form of a German mirror-maker at the Italian court, named Giovanni Deglhi Specchi, who seemed intent on stirring up trouble for the anatomist and was probably behind the problems he faced in the final years of his life when he was, in his own words ‘denounced at the hospital and in front of the Pope.’

Sadly there is no evidence that any of his findings influenced medical science whatsoever during the next 400 years, as his papers remained unpublished after his death, with all his notes further concealed by being written in his distinctive mirror-writing. Nearly 25 years later in 1543 Andreas Vesalius went on to publish his seminal work De humani corporis fabrica and claim the moniker of ‘the father of modern human anatomy’ instead of da Vinci.

More Info?

The Leonardo da Vinci Anatomist exhibition ran until during 2012 at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace Road.

If you’re keen to learn more you can download the Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomy app, which serves as a detailed interactive e-book, with all 268 drawings, interviews and 3D models – and reverses and translates the notes from mirror-Italian into readable English.

Following in Leonardo’s Footsteps?

You can also follow in Leonardo’s footsteps by visiting Vaprio, some fifteen miles East of Milan, where the exact view that Leonardo drew is still visible to visitors.

At the universities in Bologna and Padua you can still take a tour and visit the dissection rooms where studies formed the basis of modern anatomical science.

Tags: Buckingham Palace, exhibition, Leonardo da Vinci, Queen's Gallery

Trackback from your site.